What’s in a name? The Woman of Colour and Fictional Representations of the Lady’s Maid in the Eighteenth-Century Country house.

Karen Lipsedge

Turn to any eighteenth-century novel, and it is immediately apparent that domestic servants are represented as central to both the daily life of the country house and the narrative of the novel. In The Woman of Colour (1808) the protagonist’s lady’s maid, Dido, plays an equally important role. Dido is a senior domestic servant and has a close relationship with her mistress, Olivia; she is her travel companion, her confidante, and the head housekeeper of Olivia’s country residence in Devon. Unlike most of her fictional counterparts, Dido is not racially signified as white, but as ‘Black’. As the only Negro character in a domestic novel that interrogates the genre’s idealized notions of white femininity, Dido, a formerly enslaved Black lady’s maid, challenges normative notions of domestic servitude, race and ethnicity, gender and the hierarchies of power.

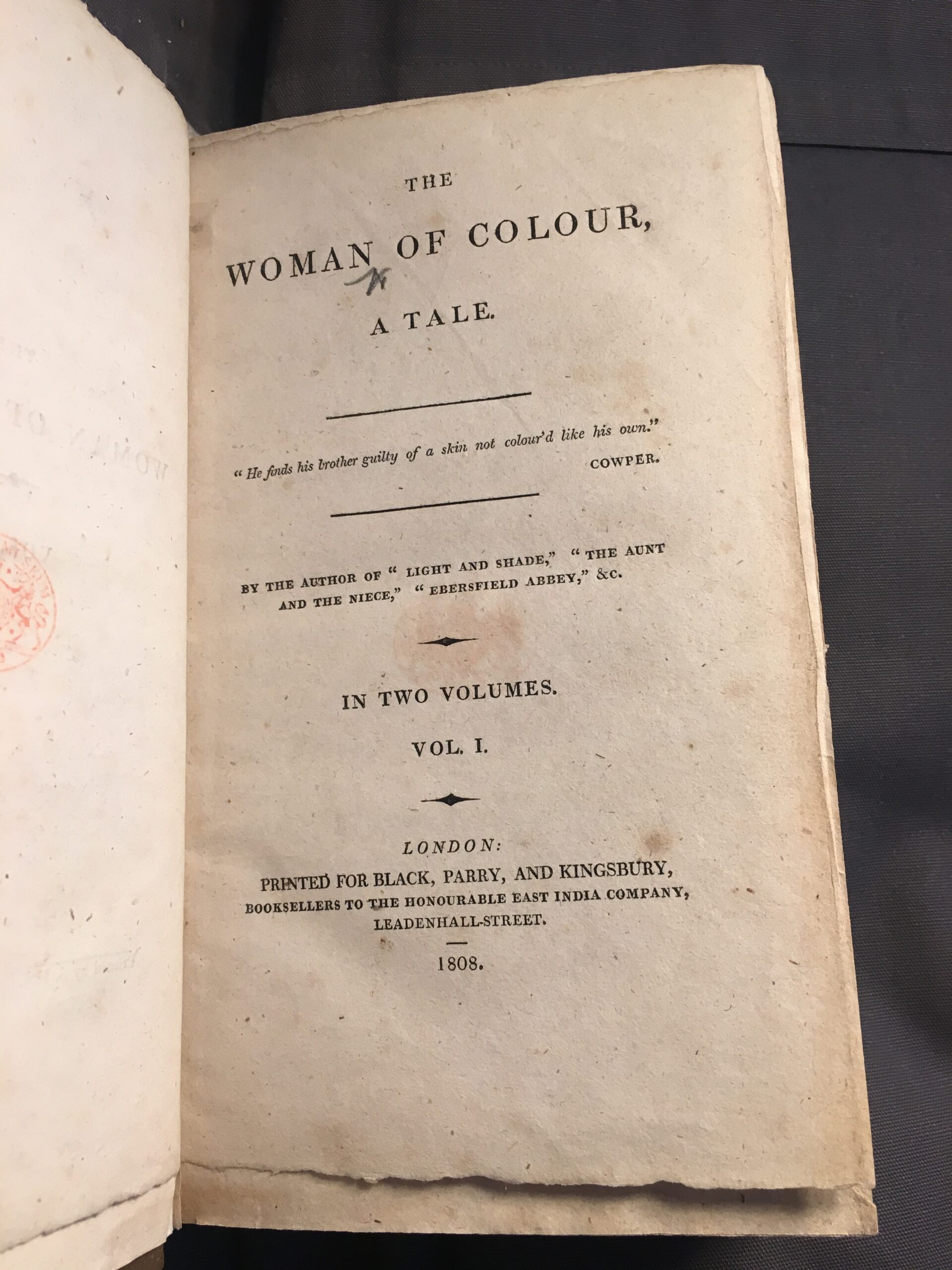

Anonymous, The Woman of Colour (1808). Title page.

Despite attempts by philosophers and lawyers, most notably William Blackstone, to make a clear distinction between a servant and a slave, the experiences of formerly enslaved Black men such as Ignatius Charles Sancho and Francis Barber, underscore that ambiguity about the state of freedom of Black servants in Great Britain remained until mid-nineteenth century.

A similar ambiguity is evident in The Woman of Colour. To most of the characters in the novel, Dido is regarded as an enslaved domestic servant and someone of a lower status than her fellow white counterparts. However, to the ‘olive’ skinned Olivia Fairfield (p.87), who is the wealthy heiress of a Jamaican slave plantation, Dido is her lady’s maid. In return, Dido’s loyalty to and affection for her mistress is unwavering. But Dido’s fidelity is also discriminating. As Dido observes to her mistress,

‘Mrs Merton’s maid treats me, as if me was her slave… and Dido was never slave but to her dear own Missee, and she was proud of that.” (p.100)

Dido’s use of the word ‘was’ is important. It highlights that Dido is cognisant that in England she is not enslaved, but a free woman and is also aware of what freedom means for a woman of African descent. Moreover, Dido’s objection to the status of slave demonstrates that she knows that she should be treated like other white lady’s maids in an English household, and not like the ‘animal’, which is how the young George claims all Black slaves should be treated. (p.80)

Dido is represented as a complex, highly nuanced character in The Woman of Colour. Yet the lives that real domestic servants, especially those of colour, led and the spaces they inhabited in eighteenth-century country houses were equally dynamic and fluid. The anonymous author’s representation of Dido in The Woman of Colour underscores the importance of naming; of the terminology used to define the status of servants and to refer to servants as individuals. The novel also sheds new light on the often-overlooked presence of Black female servants in the eighteenth-century country house. By moving discussions about black domestic servants beyond the fashionable footman/boy, The Woman of Colour demonstrates the value of fiction for furthering our understanding of servants in histories of the country house.

Further reading

- Barnett-Woods, Victoria, and Karen Lipsedge, ‘Feminisms: Intersectionality in Domestic Fiction’, in The Routledge Companion to Eighteenth-Century Literatures in English, Edited By Sarah Eron, Nicole N. Aljoe, Suvir Kaul (London: Routledge, 2023), 331-342

- Gerzina, Gretchen, Black England: A Forgotten Georgian History (London: John Murray, 1995, 2023)

- Meldrum, Tim, Domestic Service and Gender, 1660-2750: Life and Work in the London Household (Harlow: Pearson, 2000)

- Scobie, Ruth, ‘Breakfast with ‘Her Inky Demons’: Celebrity, Slavery, and the Heroine in Late Eighteenth-Century British Fiction’, Eighteenth-Century Fiction, 34, 4, 2022, 415-440.