Resources

We have compiled two sets of resources for anyone wishing to study servants’ lives in more detail: a bibliography of published work on servants, c.1700-1850, and a set of primary sources in which we offer a brief introduction to the source and its potential, plus links to where examples can be found.

-

Castelluccio, Stéphane, La noblesse et ses domestiques au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Hayot, 2021)

Chynoweth, Tessa, ‘Domestic service and domestic space in London, 1750-1800’, unpublished PhD thesis, Queen Mary, University of London, 2017

Davrius, Aurélien. ‘Masters and servants: parallel worlds in Blondel’s maisons de plaisance’, in Jon Stobart (ed.) The Comforts of Home in Western Europe, 1700-1900 (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 39-44

Fairchilds, Cissie, Domestic Enemies: Servants and their Masters in Old Regime France (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984)

Flather, Amanda, ‘The Organization and Use of Household Space for Work in Early Modern England: 1550–1750’, European History Quarterly 51:4 (2021), 480-503

Frühsorge, Gotthard, Rainer Guenter and Beatrix Freifrau Wolff Metternich (eds.), Gesinde im 18. Jahrhundert (Hamburg, 1995)

Gillis, John R., ‘Servants, Sexual Relations, and the Risks of Illegitimacy in London, 1801–1900’ in Judith L. Newton, Mary P. Ryan and Judith R. Walkowitz (eds.), Essays from Feminist Studies (London and New York: Routledge, 2012)

Gerard, Jessica, Country House Life: Family and Servants 1815-1914 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994)

Hardyment, Christina, Home Comfort: a History of Domestic Arrangements (London: Viking, 1992)

Hayhoe, Jeremy, ‘Rural Domestic Servants in Eighteenth-Century Burgundy: Demography, Economy, and Mobility’, Journal of Social History 46:2 (2012), 549-571

Hecht, J. J., The Domestic Servant Class in the Eighteenth Century (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1955)

Hill, Bridget, Servants. English Domestics in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996)

Humfrey, Paula (ed.), The Experience of Domestic Service for Women in Early Modern London (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011)

Keithan, Aimée , ‘Servants’ passage: cultural identity in the architecture of service in British and American country houses 1740-1890’, unpublished PhD thesis, University of York, 2020

Kent, David, Ubiquitous but Invisible: Female Domestic Servants in Mid-Eighteenth Century London (Oxford University Press, 1989)

Kühn, Sebastian, ‘Die Macht der Diener. Hausdienerschaft in hofadligen Haushalten (Preußen und Sachsen, 16.-18. Jahrhundert)’, in: Mitteilungen der Residenzen-Kommission der Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Neue Folge: Stadt und Hof 6 (2017), 159-169

Kühn, Sebastian, ‘Teil-Habe am Haushalt. Dienerschaften in Adelshaushalten der Frühen Neuzeit’, in: Malte Gruber and Daniel Schläppi (eds.), Von der Allmende zur Share-Economy (Berlin 2018), 113-136

Maza, S., Servants and their Masters in Eighteenth-Century France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983)

Meldrum, Tim, Domestic Service and Gender, 1660-1750: Life and Work in the London Household (Harlow: Pearson Education, 2000)

Müller-Staats, Dagmar, Klagen über Dienstboten. Eine Untersuchung über Dienstboten und ihre Herrschaften (Frankfurt/Main 1987)

Musson, Jeremy, Up and Down Stairs: The History of the Country House Servant (London: John Murray, 2009)

Richardson, R.C., Household Servants in Early Modern England (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010)

Sambrook, Pamela, Keeping Their Places: Domestic Service in the Country House (Stroud: Alan Sutton, 2009)

Sambrook, Pamela, The Servants’ Story: Managing a Great Country House (London: Amberley, 2016)

Sambrook, Pamela, and Peter Brears (eds), The Country House Kitchen, 1650-1900 (Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1996)

Sarti, Raffaella, ‘’The Purgatory of Servants’: (In)Subordination, Wages, Gender and Marital Status of Servants in England and Italy in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries’, Journal of Early Modern Studies 4 (2015): 347-372

Schröder, Rainer, Das Gesinde war immer frech und unverschämt. Gesinde und Gesinderecht vornehmlich im 18. Jahrhundert (Frankfurt/Main 1992)

Steedman, Caroline, Master and Servant: Love and Labour in the English Industrial Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007)

Stobart, Jon, ‘Housekeeper, correspondent and confidante: the under-told story of Mrs Hayes of Charlecote Park, 1744–73’, Family and Community History, 21:2 (2018), 96-111

Stobart, Jon, ‘Servants’ furniture: hierarchies and identities in the English country house’, in S. Hague and K. Lipsedge (eds), At Home in the eighteenth Century: Interrogating Domestic Space (Routledge, 2022), 245-65

Straub, Kristina, Domestic Affairs: Intimacy, Eroticism, and Violence Between Servants and Masters in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009)

Tobin, Beth Folkes, ‘Bringing the Empire Home: The Black Servant in Domestic Portraiture’ in Picturing Imperial Power: Colonial Subjects in Eighteenth-Century British Painting (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999)

Wallace, Hannah, ‘Servants and the Country Estate: Community, Conflict and Change at Chatsworth, 1712-1811’. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Sheffield, 2020

Waterfield, Giles, Anne French, and Matthew Craske, Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2003)

Waterson, Merlin, The Servants’ Hall: a Domestic History of Erddig (London: Rouledge, 1980)

Wolfthal, Diane, Household Servants and Slaves: A Visual History, 1300–1700 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2022)

-

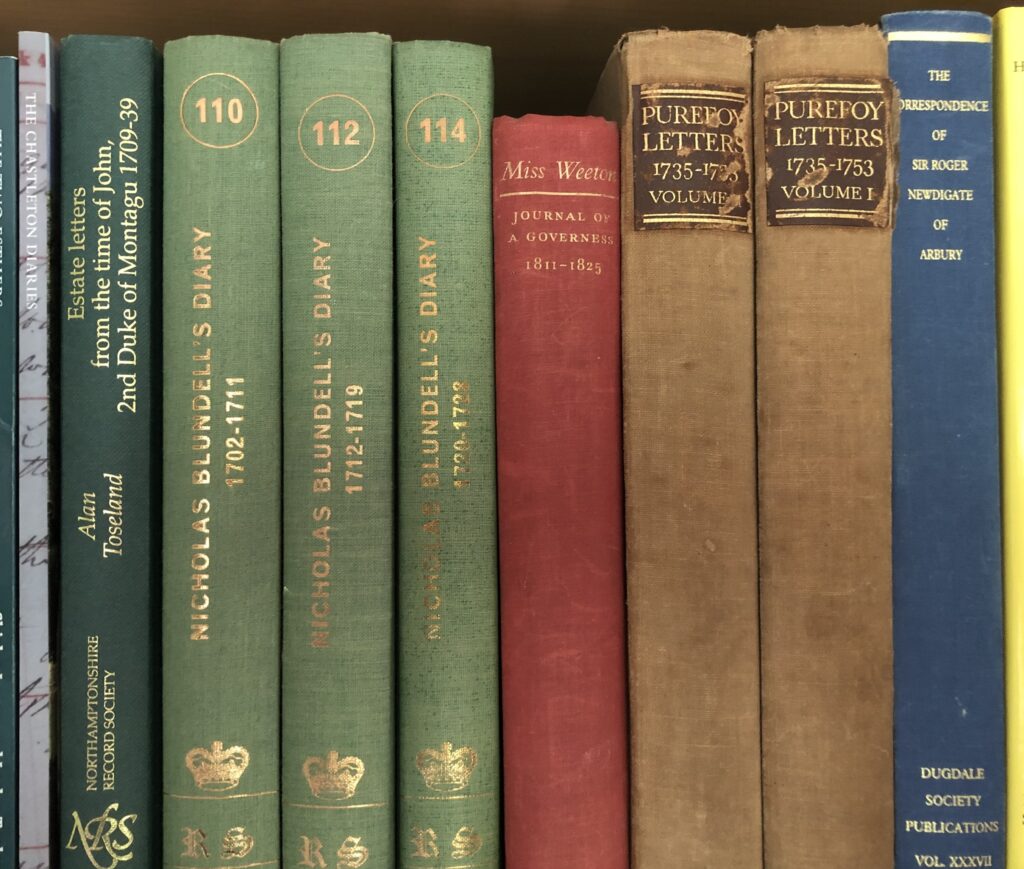

Printed sources

Conduct manuals

Conduct manuals do not offer insight into the actual but rather the ideal relationships between masters and servants in the household. The authors of conduct manuals set out ground rules of conduct which included general behaviour, but also practical advice on duties as well as moral value systems that should govern the ideal master-servant relationship. Often, they were religious in tone, using scriptural evidence to map out and cement the hierarchy between masters and servants. While the contents often followed similar lines, the authors wrote from varied backgrounds and experiences, such as education (Trimmer), being servants themselves (Samuel and Sarah Adams), or in fact satire (Swift). The intended audiences for these conduct manuals transcended the split between masters and servants, with some manuals addressing masters (for instance, Seaton), whereas others tried to instruct servants themselves (for instance, Trimmer). While conduct manuals generally emphasised the master’s power in this relationship and the servant’s duty to obey, they reminded their readers that with a master’s social and financial superiority came a responsibility towards the moral and physical wellbeing of their servants. (Sophie Dunn)

Examples include:

Adams, Samuel, and Sarah Adams, The Complete Servant (London, 1825)

Adams, Samuel, and Sarah Adams, The Servants’ Guide and Family Manual (London, 1830)

Seaton, Thomas, The conduct of servants in great families (London, 1720)

Swift, Jonathan, Direction to Servants (second edition, London, 1746); Samuel Adams and Adams, Samuel, and Sarah Adams, The Complete Servant (London, 1825)

Trimmer, Sarah, The Servant’s Friend (London, 1786)

Auction catalogues

Catalogues of country house sales were produced by auctioneers to promote the event. They provided information on the location and date of the sale, and generally of arrangements for viewing the goods in advance. Most sales took place at the house itself and the catalogues present the goods available room by room. It is impossible to know whether all the contents of the house were being sold and there are sometimes categories of goods (e.g. paintings) or sets of rooms (e.g. bedchambers) missing from the catalogues. In many cases, however, they provide detailed insight into the presence and quality of a wide range of goods contained in the house: from copperware in the kitchen to sofas in the drawing room. Sometimes, the auctioneer used additional adjectives, describing goods as elegant or handsome, or noting that they were capital or lofty. Importantly, many catalogues include the contents of service rooms, out buildings, servants’ halls and servants’ bedrooms. They list goods provided for the use of servants rather than things owned by them, but nonetheless offer important insights into material culture of country house servants. (Jon Stobart)

Collections of sale catalogues can be found at:

– British Library, London

– Northamptonshire Central Library: M0005644NL-M0005647NL

Sotheby’s provides a useful gateway to several other online collections: https://sia.libguides.com/salescatalogues/historiconline

Novels

By the mid-eighteenth century, British novelists began to depict their characters in a recognisable living space. Although servants no longer shared the same space as the family, in the eighteenth century, they continued ‘to preside over the domestic affairs’ not only in the houses of not the wealthy but also those of trade and craftsmen. Consequently, novelists’ increased attention to their characters’ daily lived experience resulted in the readers’ access to the fictional domestic lives of the household owners as well as of their servants. Indeed, in some novels, authors use increased attention on the domestic lives of servants to engage in contemporary debates about the hierarchies of social class; the increased presence of indentured labour in the home; social constructions of gender, and the importance of taste and morality. Included in the examples listed below are some novels where the servant is not just a bit part in the drama of the gentry, but the driver of the novel’s narrative and the focus of the plot (Karen Lipsedge)

Examples of British novels in which servants feature strongly:

Austen, Jane: Sense and Sensibility (1811) and Mansfield Park (1813)

Burney, Fanny: Evelina, or the History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World (1778); Cecilia: Memoirs of an Heiress (1782); Camilla; or, A Picture Of Youth (1796)

Fielding, Henry: The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews (1742)

Haywood, Eliza: Love in Excess (1719); Lasselia (1723); Fantomina (1725) and The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless’ (1751)

Richardson, Samuel: Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1742); Clarissa, or, The History of a Young Lady (1747-8); The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753)

Sheriden, Frances: Memoirs of Miss Sidney Bidulph (1761)

The Woman of Colour: A Tale (published anonymously in 1808)

Archival sources

Inventories

[under construction]

Correspondence

[under construction]

Journals

[under construction]

Journals by servants are very rare in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, but include:

English Heritage, Inventory Number 88298111, Thomas Challis Notebook, 1792-1845 (Challis was an under gardener at Audley End, Essex)

Inventories

Inventories of household belongings exist for country houses and manors across Europe. They were created for a variety of reasons including marriage and bankruptcy, but most often at the death of the house owner. They generally comprise a complete listing of the contents of the house and outbuildings, and sometimes include clothing and debts owed to the deceased. Many inventories are organised by room, although linen, glass and chinaware, and silver often appear in consolidated lists – whilst books and paintings sometimes appear in separate listings. Values are often recorded for each item, giving an idea of the relative importance of different rooms and categories of goods, and a measure of how much of a householder’s wealth was tied up in material objects. Inventories can provide important insights into the work and lives of servants. They detail the contents of service rooms, servants’ halls and bedrooms, and often buildings on the wider estate – such as lodges or stables. However, they do not list things owned by servants: the contents of their boxes, for example, remain largely hidden.

Published collections of inventories include:

James Collett-White (ed.), Inventories of Bedfordshire Country Houses, 1714-1830 (Bedfordshire Historical Record Society, 1995)

Historischer Arbeitskreis Wesel (ed.), Friedrich Freiherr von Wylich, 1706-1770. Ein preussischer Generalleutnant aus Diersfordt am Hofe Friedrichs des Großen. Eine Lebensbeschreibung, Briefe an seine Familie, besonders an seinen Sohn Christoph Alexander von Wylich nach Diersfordt, sein Nachlass, Wesel 2019

Tessa Murdoch (ed.), Noble Households: Eighteenth-Century Inventories of Great English Houses (John Adamson, 2006)

Household accounts

Accounts were central to the efficient running of country houses, from princely palaces to more modest manors. A wide variety of account books survive including cooks’ accounts of the everyday provisioning of the kitchen, servants’ wage books, and notebooks recording the personal expenditure of owners or family members. These were often organised as ledgers, noting expenditure as it occurred day to day. More comprehensive were the general household or estate accounts. These were kept by the owner or their steward and generally formed summary accounts, organised by area of spending – for example: house, cellar, garden and stables. Some also record income from the estate, although it seems that there was often little concern with balancing the books. Whilst they vary hugely in their scope and the thoroughness with which they were kept, household accounts provide a huge amount of information on patterns of spending, the changing costs of goods and services, and so on. Servants permeate the pages of account books: the wages they were paid, the cost of their boarding and livery, and the equipment and products they required for their work – from soap to curry-combs.

A good example of this kind of noble accounting are the diaries of the Bavarian baron Sebastian von Pemler: Barbara Kink, Adelige Lebenswelt in Bayern im 18. Jahrhundert. Die Tage- und Ausgabenbücher des Freiherrn Sebastian von Pemler von Hurlach und Leutstetten (1718 – 1772), München 2007.

Useful examples in archives include:Archiv Schloss Dyck (Germany), Rechnungs- und Aktenbestand der Zentralverwaltung mit der Überlieferung zu den Rittergütern Alfter, Dyck, Hackenbroich, Herschberg, Neucilli (1806–1914)

Brandenburg Landeshauptarchiv (Germany), Rep. 37 Herrschaft Lübbenau, Kr. Calau Schloss- und Ökonomierechnungen (1753-1822)

Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg (Germany), STAL PL 12 III Hohenstadter Rechnungen (1686-1741, 1806-1862

Warwickshire Record Office (UK), CR136/v/156 (1747-62) and CR/v/136 (1763-96), Sir Roger Newdigate’s Accounts

Lists of servants

A country house could not be run without the help of servants. Depending on the size of the house and the owners’ means, servants’ numbers could range from just a maid, a cook and a “jack of all trades” to several dozens with highly specialized skills. Lists of servants give insight into the inner fabric of the household and the owners’ means and attitudes; they provide notions of possible career trajectories, such as from kitchen help to kitchen maid to finally the position as cook. Servants’ lists, or rather lists of their wages, are recorded in the general account books of many estates. Sometimes, owners preferred to keep proper servants’ books, detailing the shifting number of servants, their length of stay and sometimes career trajectory (Anne Sophie Overkamp).

Lists of servants are occasionally included in publications, for example: Mark Giroaurd, The Country House Companion (New Haven, 1987)

A good example of accounts of an English estate showing servants’ wages is:– Warwickshire Record Office, CR136/v/156 (1747-62) and CR/v/136 (1763-96), Sir Roger Newdigate’s Accounts

Some examples of servants books from Germany:– Archiv Schloss Heltorf, N2 65a, Offizianten- und Domestiquenbuch (1785-1796)– Archiv Schloss Dyck, Bestand 45, No. 158, Livrées, Habits, Argents donnés aux gens attaches à la maison (1822-1858)

Visual sources

Paintings

[under construction]

Satirical prints

The satirical print market boomed in Britain from the mid eighteenth century onwards, with large numbers of single sheet etchings, engravings and mezzotints sold through print shops, via advertisements and subscriptions, and by street hawkers. Typically available hand coloured for a little additional money (1 shilling plain, or 2 shillings coloured was a standard price), they were available from provincial vendors as well as in London, the heart of the trade. However, these prints didn’t have to be purchased to be seen: they were also available to view in many coffee houses and inns, and up on display in shop windows.

The prints of most significance here are the social satires published by the likes of Carington Bowles, Samuel William Fores, and Robert Sayer and John Bennett, lampooning characters and situations, manners and mores. Sometimes servants appear in purely supporting roles, moving chairs or bringing kettles of hot water to refill tea pots. When they play a more crucial part in the action, they might stand at a doorway, peering into rooms at their employers engaging in foolish or illicit activities, drawing on the ubiquity of their presence in middle and upper-class households. Many show attractive serving maids being variously seduced or molested by their masters; a smaller number show mistresses doing likewise with their male servants. This common theme of the sexual vulnerability of the servant class, seen through a regrettably humorous lens, is most pronounced in the ‘Statute Hall for Hiring Servants’, published by Sayer in 1770. (Kate Retford)

Digitisation projects have made vast quantities of this material available online. Many collections include relevant material, such as that of the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Rijksmuseum, but the two most significant resources are:

1. the British Museum – https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection – excellent search functionality, and thousands of images available high resolution

2. the Lewis Walpole Library – the Library’s collections include particularly important holdings of eighteenth-century British prints and drawings, and include the largest number of visual satires outside the UK. These have also been extensively catalogued and digitised – https://collections.library.yale.edu/