Selling servants’ furniture: Lillington Dayrell, 26 May 1800

Jon Stobart

Country house auctions were a key mechanism for the recirculation of goods in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. At grand houses, like Cannons (1747) and Fonthill Abbey (1823), they offered the chance to acquire high quality and often unique items, made by the best craftsmen. More modest properties, such as Lillington Dayrell, also contained some quality pieces, such as an inlaid commode-front sideboard and a ‘very good’ mahogany framed sofa. Yet every country house sale, large or small, included numerous quotidian items found in the kitchen, cellars, garrets, and outbuildings.

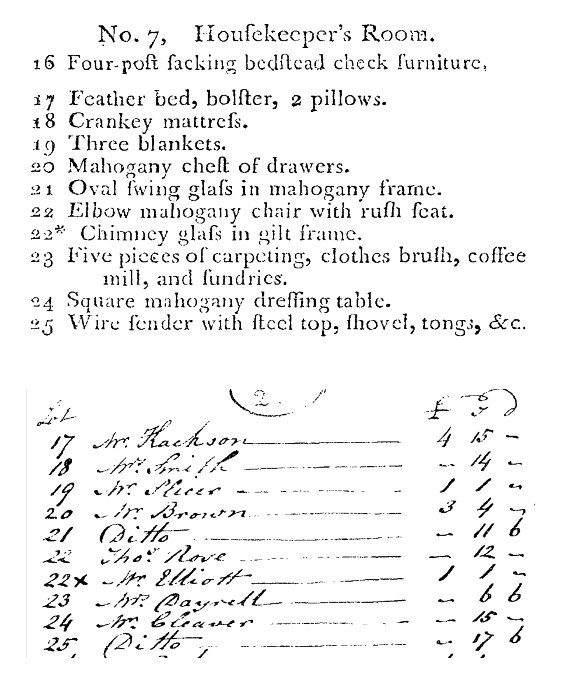

Catalogues, like the one illustrated here, listed all these items, generally arranged room by room and organised into saleable lots.

Auction catalogue for Lillington Dayrell (26 May 1800), courtesy of the British Library

They were key promotional devices: an opportunity to present the goods in a positive light before they had even been seen by prospective buyers. While some auctioneers waxed lyrical, John Day, the man in charge at Lillington Dayrell, limited himself to noting the material from which the furniture was made; something which he did in the service areas as well as the principal rooms. We thus see that the housekeeper’s room contained a typical set of furniture: a well-furnished bed, a chest of drawers, two mirrors, a chair and dressing table (all in the increasingly ubiquitous mahogany) as well as fire irons and some carpeting. These things afforded the housekeeper a little comfort and convenience.

The sale accounts – which, unusually, are interleaved with the catalogue for Lillington Dayrell – show that the furniture in the housekeeper’s room sold for a total of £17 12s. 6d. This is a respectable sum, but well below the £55 7s. 6d. realised by the contents of the Best Bedroom. The lower value of furniture in a servant’s room is unsurprising, as is the fact that those buying in the Best Bedroom did not make purchases from the housekeeper’s room. More telling, there is no sign that people were buying sets of goods in either room. The various elements of the housekeeper’s bed, for instance, were acquired by four different people and only Mr Cleaver bought more than one item from the room. At Lillington Dayrell at least, an auction formed the opportunity to buy selected items rather than furnish a whole room.

Further reading

- Blondé, Bruno, Alessandra de Muller and Jon Stobart, ‘Aesthetics for a polite society: consumer cultures and the marketing of second-hand goods in eighteenth-century London’, Economic History Review (published online, 2023).

- Pennell, Sara, ‘All but the kitchen sink: household sales and the circulation of second-hand goods in early modern England’, in Jon Stobart and Ilja Van Damme (eds) Modernity and the Second-Hand Trade (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 37-56

- Stobart, Jon, ‘Domestic textiles and country house sales in Georgian England’, Business History, 61:1 (2019), 17-37.