Back stairs in the London suburban villa

Alyssa Myers

The country house was only one within a larger network of residences that the wealthy British elite might own. It may have been the pièce de résistance as the largest house with a substantial estate, but they would also need a townhouse for the winter (parliamentary) season in London which could be owned, rented or borrowed. During the eighteenth-century, another house became desirable to possess: the suburban villa. This was typically a smaller ‘retreat’: a modest house with constrained grounds that was easily accessible from London and frequently found in areas such as Richmond, Twickenham and Putney Heath.

Having several houses naturally meant an array of servants to keep them running. One way that an owner could create a level of separation from their servants was through multiple staircases.

Large country houses had enough space to fit in several staircases. Traditionally, the grand staircase served as a status symbol that guests would have to physically climb to reach the principal rooms on the first floor. In the eighteenth century, as the principal entertaining rooms moved to the ground floor, the grand staircase remained as a dynastic reminder and was used as a show piece. At the same time, back staircases became a necessity to keep the servants visually out of sight and remove the possibility of passing them on the main stairs.

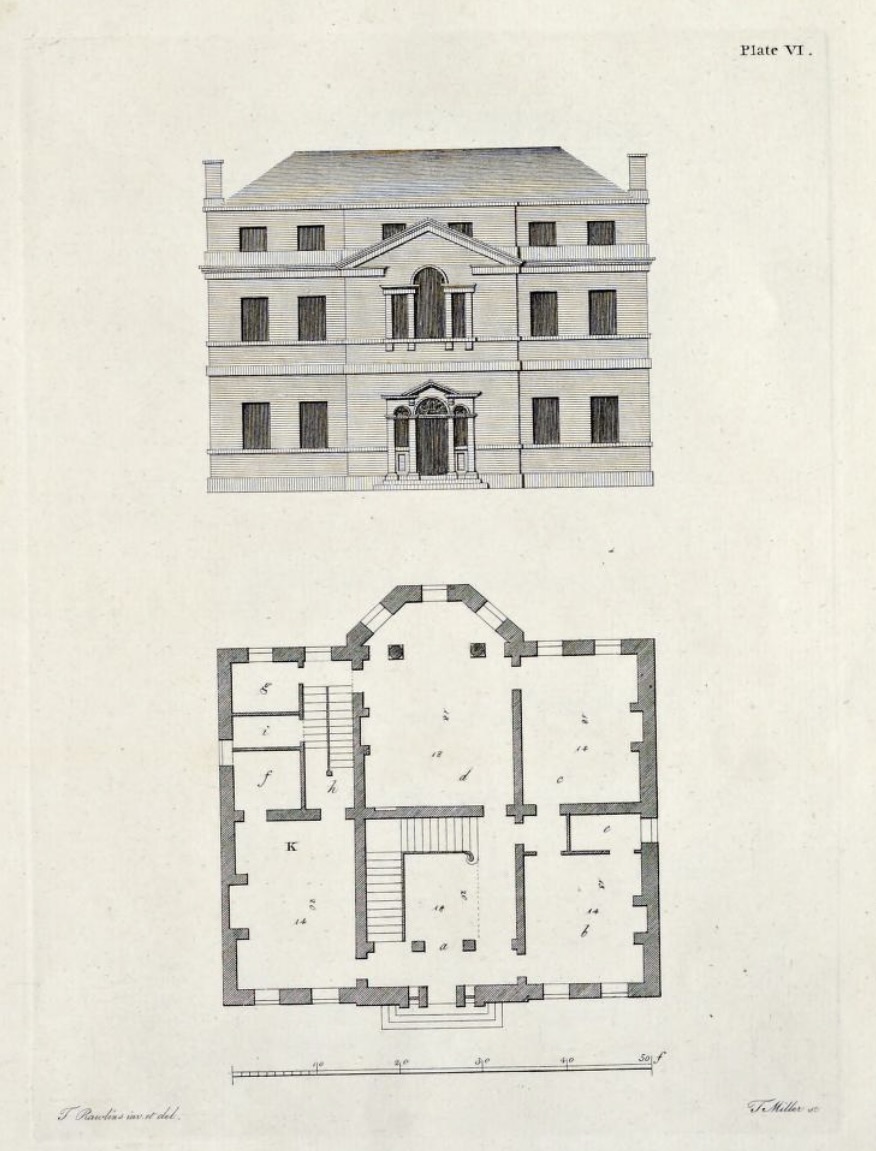

Suburban villas were much smaller and needed to maximise space. The typical villa floor plan was inspired by the Italian Renaissance villas of Andrea Palladio: symmetrical with a main entrance hall through a portico, containing a central axis point, with the principal rooms located around. The main staircase was often at the centre of that axis, as pictured in Thomas Rawlins’ plan of an urban villa. Servant’s spaces were either confined to one side of the house (as in Polwarth Lodge, Lady Amabel Hume-Campbell’s late eighteenth-century villa in Putney Heath), concentrated to the basement level, or pushed to a separate outbuilding (for example, Chiswick House, which utilised both the basement and an attached outbuilding). Despite the smaller size of these villas, they still contained a separate staircase for servants. At Polwarth Lodge, this was situated amidst the servant’s area, only separated from the main staircase by the housekeeper’s room. Yet this still provided two distinct routes through the villa: one for the family and guests and the other for servants. This was seen as essential to maintain a degree of separation and privacy, befitting the owners rank.

Further reading:

- Christie, Christopher, The British Country House in the Eighteenth-Century (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2000).

- Paston-Williams, Sara, The Art of Dining: A History of Cooking & Eating (London: National Trust, 1993).

- Stobart, Jon, Comfort in the Eighteenth-Century Country House (New York and London: Routledge, 2022), chapter 1.

You may also be interested in: The hidden pathways of servants: circulation at Florence Court, co. Fermanagh